Ca dépend!

Epilogue to the French translation of Architecture Depends

Twenty years after I started to write Architecture Depends, I am thrilled that it is being translated into French by Editions de la Villette. I was asked to write an epilogue to the translation (in print in April 2025), and this was my response. It felt emotional to go back to the original text, so this is quite personal and reflective…

It has been twenty years since I took a sabbatical year to research and then write Architecture Depends. Much has happened since then—to the planet, politics, and the profession—so my worry might be that the book’s argument has become dated and irrelevant. Yet, the fact that it is even now being translated in 2025 suggests that the book still resonates. This endurance may be for several reasons. First, the arguments were not reliant on fashionable themes or passing styles. Dependency and contingency are permanent conditions of both human life and professional practice. The book’s central premise is straightforward, almost laughably simple. Architecture Depends: get over it and deal with it. Its originality is that no one had really had the gall to put that down quite so bluntly. It may be too obvious, but nonetheless, it is an enduring message worth repeating. Second, the conditions of the discipline and profession described in the book persist today. The text serves as a necessary antidote to architecture’s continuing self-absorption, which is marshalled by the architectural media, awards systems and protectionist professional bodies. Charles Holland in an early review suggested the book was too facile in picking off ‘straw men’, caricatures of easy targets that were quickly shot down. I have since often worried about this, but then I would read an article, listen to a lecture or witness an educational event—and the separation, weirdness, and hubris of architecture came rushing back in. In such moments, I think I didn’t go far enough. The book does not describe caricatures but some norms of architecture.

The real concern is how resistant these disciplinary norms are to change. In my subsequent book Spatial Agency, written with Nishat Awan and Tatjana Schneider, we opened up the field of architecture by showing why and how other ways of doing architecture are necessary and possible. There are countless ways to deploy spatial intelligence beyond designing buildings, and this expanded scope presents new opportunities for the discipline. While many spatial practitioners have embraced these possibilities, the core of architecture remains stubbornly fixated on building production. More troublingly, the culture of architecture has largely retained a distance from the societal imperatives that surround it. Women, in particular, face ongoing discrimination through the exploitative working patterns of mainstream practice, with large international firms still overwhelmingly led by male partners. The situation is still worse for people of colour. Despite a flurry of activity after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement, the discipline in Europe and North America remains predominantly white in both composition and culture. In terms of the environment, so called ‘sustainable’ architecture has become mainstreamed in the twenty years since Architecture Depends was written. The term has become largely meaningless as it is washed across projects in petro-states and casually applied to conspicuously carbon-intensive construction. Architectural awards continue to prioritise taste and innovation over environmental impact—a proper carbon assessment would disqualify almost every major European award winner of the past decade. In all these issues of gender, race, class and environment, the profession and architectural education—with some notable exceptions—have not opened up to their dependency. As a result, they’ve become increasingly irrelevant, even impotent, as others step in to fill the void. For this reason, the argument of the book still has relevance as an urgent call for the discipline to abandon its self-defined Eurocentric boundaries, and so open up to the socio-political context in which architecture is situated.

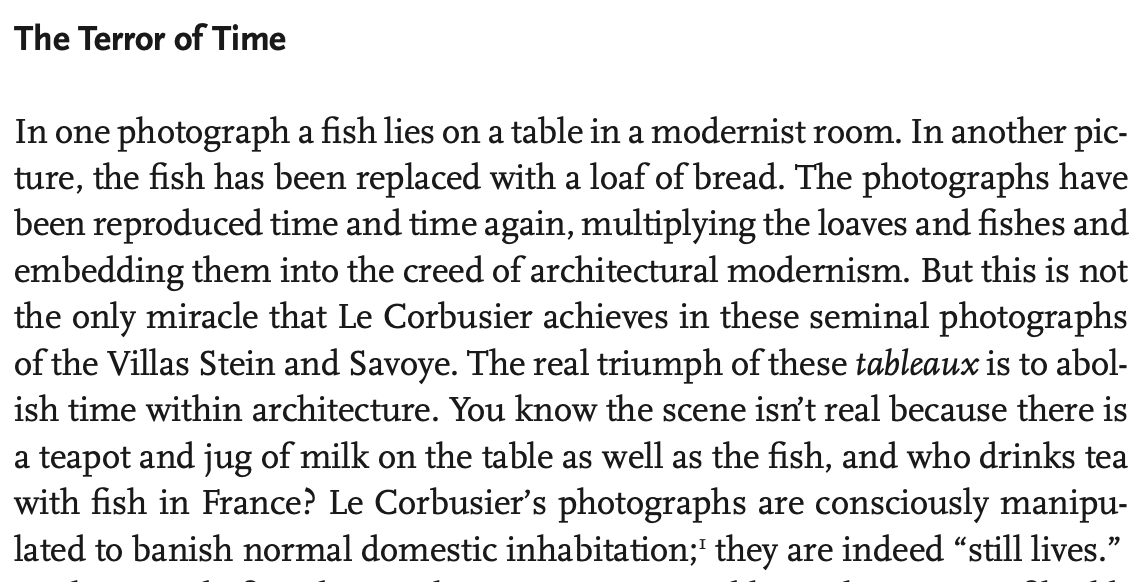

What, then, might I change if I had another go at writing it now? The immediate answer is: everything. Writing a book, like designing a building, is completely bound to its temporal, spatial, personal and social context. What emerges is a product of these conditions. For instance, rereading parts of the book recently, I was struck by the intensity and (though I say it myself) fluency of some of the writing. I look at the opening paragraph of Chapter 5 (On Time)…

…and am both proud of the words and regretful that I have never reached that pitch again. A whole year of concentrated focus gave the book a rhythm that seems impossible to replicate. That said, I am conscious that some sections are over-laboured, particularly in the more ‘philosophical’ sections (a note to readers: feel free to skip Chapter 3; it is pretty heavy, and there is juicier stuff once you have climbed over this mountain). This density is probably because this was my first sole-authored book and (like all academics, bound to conventions) I was then a risk manager, always looking over my shoulder to cover my intellectual back. Another reviewer, Andrew Leach, said it would have been better at half its length, and I’m inclined to agree. He also suggested that ‘my hunch is that the book as published will not affect the discussion as it should, that it will be read by academics who agree with it. I would, however, very much like to be wrong.’ I hope this translation repays his faith.

Despite these reservations of mine, the book was generally well received upon publication and continues to sell (and to be photocopied…). It remains, however, a ‘Marmite’ book—an English term that means you either love it or hate it, and nothing much between. The book’s irreverence annoys the serious brigade, and its challenge to disciplinary norms raises professional hackles. Roger Conover, my editor at MIT Press (to whom I owe an immeasurable debt for having complete trust in me), recounts how he was engaged in a ferocious stand-up argument at Harvard shortly after the book’s publication. Apparently, it was an affront to some of the Graduate Design School’s hallowed members and MIT should never have published it. Roger was also once a boxer, as well as a poet and the most influential editor of his generation; I am guessing he won that fight. On the more positive side, I am always touched when people have come up, and still come up, at the end of a lecture and thank me for writing it. Usually this is because they have found a small amount of solace in the book when they have been exposed to the strange and sometimes malevolent rituals of architectural education. No one book is going to overturn the institutional structures of an established profession with vested interests, but if it can help and support some individuals, then that is all one can ask for as an author.

There is, however, something that is quite clearly missing from the book. Climate. It is there implicitly, but I would now foreground the ecological crisis throughout the book. The way architecture is complicit in climate breakdown, and its relation to the violence of capitalism and colonialism, would fit into the argument without breaking it. My most recent work, with the research collective MOULD, makes clear that climate is architecture’s greatest dependency and challenge, that Architecture IS Climate. Climate breakdown is not a problem that can be ‘solved’ by architecture; any claims to this effect are blind alleys. As we argue in MOULD, the ecological crisis undoes all the foundational tenets of the modern project—of progress, growth, extraction and separation from nature—and so invalidates the guiding principles of ‘modern’ architecture as we know it. The contingencies of climate breakdown thus call for a completely reconsidered discipline, profession, culture and education for architecture. All I can ask now is that when you read the book, you weave climate into the thread of the argument. And then take action. I never intended Architecture Depends to be a work of passive theory. Right now, in early 2025, I would like to think of it as a wake-up call. Because, unless we act collectively against the autocratic forces that are now driving ecological and democratic collapse, this book and many others will have little relevance in another twenty years’ time.